Over the past few million years evolution has moulded our bodies; changing us from an animal that looked very similar to an ape into one that looks slightly less like an ape. Evolutionary psychology claims that a similar thing has happened to our minds; and attempts to figure out which of our behaviours have been influenced by evolution and how. EvoPsych an approach with a lot of potential – after all, figuring out why we behave in certain ways could help us understand why our thought processes sometimes go wrong – but it’s also a field that really annoys me because a fairly major issue undermines a lot of research on the topic. About 65% of the research, to be exact.

What makes me especially annoyed is that this flaw is not inherent to EvoPsych. It’s not some fundamental problem that can’t be rectified, but a purely artificial issue that is rendering a large body of work effectively useless. But in order to get you to join me in my frustration (because if I am unhappy, other people should be unhappy) we need to back up a bit.

The first step in any EvoPsych investigation is to try and figure out which of our behaviours have been influenced by evolution, rather than education or culture. After all, our brains are incredibly flexible organs, capable of adapting to many circumstances. How to do this? Natural selection provides the answer. Animals with beneficial traits will fare better in the environment and have more babies, spreading those traits around the population. So if you want to spot something with an evolutionary history, you should look for stuff that appears to be effectively universal in a species. This works for our bodies, as well as behaviour. After all, bipedalism evolved and as a result everyone normally walks about on two legs.

So far, so good; but here is where the problem emerges. If you were to design an experiment to try and identify behaviours that were widespread, if not universal, in humans how would you do it? You’d take a sample from a range of populations and test to see if they behaved the same way. The problem is that this costs a lot of money, since you’d have to travel all over the world to get a suitably wide sample. So instead, many psychologists work with local populations. And most psychologists live in the West, so most of them are only looking at Westerners (or as they’re sometimes called people from Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich Democracies; because that creates an amusing acronym. WEIRD).

In fact, a study in 2008 found that 96% of research published in six of the top American psychological journals only examined WEIRD people. For some context, WEIRD people only make up around 12% of the population of the planet. And this is the big problem: researchers are trying to find “universal” behaviours but are only looking at a small group of us that is not representative of humans as a whole1.

Now, this study was looking at psychology as a whole. Breaking it down and focusing purely on EvoPsych journals seems to paint a better picture. One researchers response to the 2008 study, for example, examined an EvoPsych journal – Evolution and Human Behavior – and found that they exclusively used WEIRD participants in only 65% of research; a much more respectable number. However, that’s only one journal. I took a look at the latest issue of Evolutionary Psychology (the journal on whose website the aforementioned response was published) and of all the experiments on human participants published, every single one of them used WEIRD people.

It’s clear evolutionary psychologists are aware of the issue using WEIRD people raises (and seem to be on the cutting edge of psychology when it comes to removing it), but it is still seem to be a prevalent problem. This reliance on WEIRD people, whether in 100% of cases, 65% or 96% means that the research is being conducted on an un-representative sample.

If we were to take a similarly small sample with other topics, we might come up with some wacky results like…

- Everyone is left handed (10-30% of the population)

- Everyone is gay (2 – 20% of the population, depending on question asked)

- All Americans have encountered a ghost (22% of the population)

- Everyone in the UK lives in London (11%)

In short, I think it’s pretty clear that studying such a small portion of the population probably isn’t going to tell us much about that population as a whole; but if that isn’t obvious there are numerous cases where people have begun looking for “universal” traits identified in WEIRD populations in other groups and failed to find them. For example, a lot of WEIRD research discovered that a lot of people found a certain facial structure was attractive. So sexual selection influenced the evolution of our faces! At least, that’s what we thought until people from other cultures were asked. Turns out this isn’t actually a universal, evolved preference; just a Western cultural one.

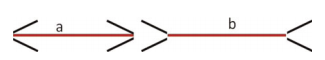

The Muller-Lyer illusion. The two lines are the same length, but don’t look it. People from different cultures are more/less fooled by the illusion

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. That 4% of non-WEIRD research has revealed numerous more differences between WEIRD people and the rest of the world. Even some stuff you might think is actually innate. The Muller-Lyer illusion (see picture above) affects people from different groups differently. Some hunter-gatherers, for example, aren’t even fooled by it! You’d think that illusions, which are tricking our brains, would be universal. We all have very similar brains after all. WEIRD people are also less driven to conform, more likely to make moral judgements based on consequences and tend to be a bit fairer when divying up prizes between groups of people….the list goes on2.

These are all behaviours which most EvoPsych research would identify as universal (and thus perhaps evolved) but is actually influenced by culture, education and experience. And unless you study people from a range of cultures, educational backgrounds and so forth; you’re not really going to be able to figure out which behaviours have evolved. Don’t get me wrong. Examining WEIRD people is cheap and efficient, and is a good way of throwing a lot of ideas at the wall to see what sticks. But without a follow-up demonstrating that whatever does stick is actually universal, it remains a hypothesis.

And that’s why I’m frustrated with evolutionary psychology; and why you should be too. And why, unless you see research that has a broad sample, it can’t tell us too much about our evolution. Which sadly, seems to be the most of the research.

References & notes

- Arnett JJ. (2008). The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. American Psychologist , 63, 602–614

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world?. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61-83.

EDIT NOTE: This post originally talked about 96% of research using WEIRD people. That was based on studies looking at psychology as a whole. Looking at EvoPsych research in particular seems to suggest they are slightly better, with a study of one journal suggesting it may be as low as 65%. I took a quick look at another journal though, and this seems to be a bit on the low side. Nevertheless, I’ve updated the post with a discussion of all this, and to use the new, lower figure in the title.

I wonder what effect global media has (and will continue to have) in smoothing out some of those differences. I suspect the world will become increasingly WEIRD…

Or might WEIRD get normal-er, as ideas from around the world are given greater prominence in Western culture?

No doubt ideas go both ways, but there is something powerfully seductive and dynamic about western civilization, so I suspect we’ll infect the world more with our memes than we will be affected by theirs.

In fact, I wonder if the power of western civilization comes, at least in part, from how we tend to take the bits and pieces of other societies we find most useful (while discarding the traditions and culture that come with them) and bend them to our uses. We end up being a hybrid composed of the effective parts, yet not being bound by tradition or culture.

Well if you look at the Romans, they seem to have had a similar strategy; incorporating all sorts of beliefs and ideas from the people they conquered. And it worked well for them for many years. Which always makes me wonder if there were other parallels between their culture and ours. Perhaps a bunch of Romans complaining about how back in their day it was Poseidon, not Neptune.

Although I suspect that our technology might have more to do with it. People always want a slice of that pie.

Heh, good analogy, and you may be right about other parallels. As I understand it, the Romans had pretty good “technology” for their day.

I’m not terribly familiar with the history of the Roman Empire, so I took a look at a couple Wiki articles, and some of the parallels seem almost eerie.

Two-hundred years of stability and prosperity followed by a crisis involving invasion, disease, civil war and economic turmoil. A rise in religion and a fall of literacy. A growing division between wealth and the citizens.

I’m going to have to read more about this. There seems to be many echos of present day.

I’ve heard of a theory involving the lead in their water pipes contributing to their decline… their own technology was part of their downfall. Which brings me to cell phones and the interweb….

If you want to be even more worried, check out “collapse” by Jared Diamond.

Looked him up, and I see what you mean!

You really should read David Buss’ EP textbook (4th edition, 2012). Among the many researchers whom he thanks for their input is WEIRD co-author Henrich. Also, the WEIRD article itself might be worth re-visiting:

http://www.epjournal.net/blog/2013/09/is-evolutionary-psychology-weird-or-normal/

You might recall that Buss’ research on sex differences in mate preferences numbers uppermost in the WEIRD article among cross-cultural findings that withstand scrutiny.

I’ll check out the book if I have a chance, always looking to give my eyes something to do.

As for the other data, I wasn’t aware of it. I’ve amended my post to use the lower figure, however I suspect it might be an under-representation of the prevalence of WEIRD in EvoPsych as it only examines one journal. I took a look at the latest issue of Evolutionary Psychology (on whose website that new stuff was posted) and of all the studies on human participants, every single one of them used WEIRD people.

Granted I was only looking at a handful of their articles. It would be interesting to see the results of a more widespread review of EvoPsych literature. I might do such a thing, perhaps write a follow-up. What journals would you recommend as perhaps being representative of (or the best) in the field? For context, the 2008 study looked at six.

The real and interesting debate, as far as I can tell, is between EP and researchers in cultural evolution (among whom Henrich prominently numbers); but this is a debate *within* a generally shared evolutionary framework. PJ Richerson has a very nice exposition:

Click to access Brown&Richerson_revised.pdf

Hi. I’d like to ask why you choose to focus on Evolutionary Psychology (EP) in particular, instead of directing this criticism at psychology as a whole?

The key point in your argument is this: “a study in 2008 found that 96% of research published in six of the top American psychological journals only examined WEIRD people”. So I’m wondering why, since the study was about psychology journals in general, you choose to focus your criticism at EP in particular.

I don’t know if you know that your complaint isn’t a new one. Evolutionary psychologists have replied to it before. In fact, they’ve gone further, and crunched the numbers comparing EP with neighbouring branches of psychology. What that data shows is that EP actually does *more* cross-cultural work than neighbouring branches of psychology: http://www.epjournal.net/blog/2013/09/is-evolutionary-psychology-weird-or-normal/

So why focus on EP in particular?

I focus on EP because I’m interested in evolution, so that’s the aspect of psychology I’m most interested in (and would most like to see improved. When done right it can offer an unparalleled look into our species past).

As for the other data, I wasn’t aware of it (although I was aware I’m not making a novel argument. I just wanted to collect my thoughts on the subject into one place). I’ve amended my post to use the lower figure, however I suspect it might be an under-representation of the prevalence of WEIRD in EvoPsych as it only examines one journal. I took a look at the latest issue of Evolutionary Psychology (on whose website that new stuff was posted) and of all the studies on human participants, every single one of them used WEIRD people.

Granted I was only looking at a handful of their articles. It would be interesting to see the results of a more widespread review of EvoPsych literature. I might do such a thing, perhaps write a follow-up. What journals would you recommend as perhaps being representative of (or the best) in the field? For context, the 2008 study looked at six.

Psychologists and neuroscientists of many stripes assume the mechanisms and processes they study are common to all humans. Ev psych does somewhat better at taking a broader view, see e.g., http://www.epjournal.net/blog/2013/09/is-evolutionary-psychology-weird-or-normal/

Also, some evolutionary psychologists are very much interested in culture (social learning), as well as in cross-cultural and within-cultural variation in behaviour and cognition. It’s not about identifying universals, un-“influenced by culture, education and experience”.

To take a random snapshot, the current Evolution and Human Behaviour has evolutionary psychologists studying

– within culture variation in mating preferences (Lukaszewski et al)

– interaction of behavioural immune system and cultural identity (Lund et al)

– large representative samples (8k people, Hubner & Fieder)

– comparisons of attractiveness in forager (Hadza) and industrial societies (Wheatley et al).

The 4% get a lot of space there.

EvoPsych peeps are aware of the WEIRD issue and are at the cutting edge when it comes to trying to reduce it. However, that “broader view” only examines one EvoPsych journal (compared to the 6 examined in the original study). I took a look at the most recent issue of another (Evolutionary Psychology in which that broader view was published) and found every single one of the studies on human participants used WEIRD people.

EvoPsych does seem to be trying to solve the problem, and are making good headway in giving it the attention it deserves. It nevertheless seems to remain a problem.

You are absolutely right on that account, Adam. This is the focus of my work and your post confirms what I am writing on. Psychological research (not just evolutionary) is absolutely flawed on most accounts.

I don’t know if it is still true, but when I was studying psychology, most research was done on college freshmen. Really representative. And unless they were specifically loooking at something related to class differences. Most subjects were middle class.

Pingback: Why you shouldn't trust 96% of Evolutionary Psychology | EvoAnth | NewsPsicologia.com

If research reveals differences between WEIRD people and non-WEIRD, it does not necessarily means the difference is due to a culture and environment. It may well mean that WEIRD and non-WEIRD people have innative differences in brain structure as well.

I am often annoyed by people quoting some differences between populations and then stating “see, this has to be due to differences in culture”, ignoring the fact that populations may in fact be genetically inclined to different behaviours.

That’s a possibility, but I suspect a slim one. The human brain has been shown to be very plastic and very capable of being moulded by culture; so I think that should be the null hypothesis when considering cultural differences

Yes, human brain is plastic and moulded by culture; but still, given substantial heritabilities of almost any trait one can imagine within group, I would say that at least for some traits, the null hypothesis should be that genetic differences have some (though possibly small) influence too (e.g. the known thing about temperament differences between asian and european children, appearing before they start to walk)

And how would we establish which behaviours should have a null hypothesis of genetic causes; and which should have cultural causes?

Your example, I think, betrays the answer: looking for evidence that a particular behaviour does appear to be innate and influenced by genetics. In which case the claim of a genetic basis would not be the assumed, null hypothesis, but an evidence-based idea. In other words, culture should be assumed (particularly given how easy it is to mistake cultural influences for genetic ones) but it is an assumption which can be overturned with evidence.

I would say null hypothesis should be culture+genes, particularly given how easy it is to mistake genetical influence for cultural ones 🙂

Pingback: Does buying your date dinner work? (or, “the second big reason you shouldn’t trust evolutionary psychology”) | EvoAnth